|

Photo by David Preston What is a floating deductible? Excess of Loss contacts for Aviation books, specifically those covering airline risks (planes with more than 50 seats) often use a special type of deductible, called a floating deductible. Instead of applying a fixed amount to the loss in order to calculate recoveries, the deductible varies based on the size of the market loss and the line written by the insurer. These types of deductibles are reasonably common, I’d estimate something like 25% of airline accounts I’ve seen have had one. As an aside, these policy features are almost always referred to as deductibles, but technically are not actually deductibles from a legal perspective, they should probably be referred to as floating attachment instead. The definition of a deductible requires that it be deducted from the policy limit rather than specifying the point above which the policy limit sits. That’s a discussion for another day though! The idea is that the floating deductible should be lower for an airline on which an insurer takes a smaller line, and should be higher for an airline for which the insurer takes a bigger line. In this sense they operate somewhat like a surplus lines contract in property reinsurance. Before I get into my issues with them, let’s quickly review how they work in the first place. An example When binding an Excess of Loss contract with a floating deductible, we need to specify the following values upfront:

And we need to know the following additional information about a given loss in order to calculate recoveries from said loss:

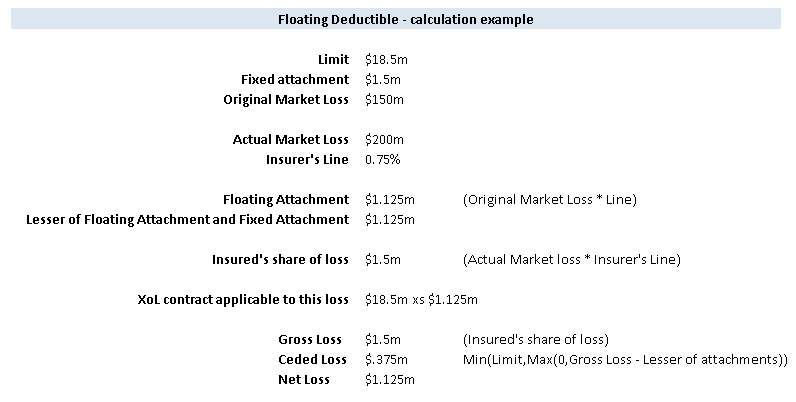

A standard XoL recovery calculation with the fixed attachment given above, would first calculate the UNL (200m*0.75%=1.5m), and then deduct the fixed attachment from this (1.5m-1.5m=0). Meaning in this case, for this loss and this line size, nothing would be recovered from the XoL. To calculate the recovery from XoL with a floating deductible, we would once again calculate the insured’s UNL 1.5m. However we now need to calculate the applicable deductible, this will be the lesser of 1.5m (the fixed attachment), and the insurer’s effective line (defined as their UNL divided by the market loss = 1.5m/200m) multiplied by the Original Market Loss as defined in the contract. In this case, the effective line would be 0.75%, and the Original Market Loss would be 150m, hence; 0.75%*150m = 1.125m. Since this is less than the 1.5m fixed attachment, the attachment we should use is 1.125m our limit is always just 18.5m, and doesn’t change if the attachment drops down. We would therefore calculate recoveries to this contract, for this loss size and risk, as if the layer was a 18.5m xs 1.125. Meaning the ceded loss would be 0.375m, and the net position would be 1.125m. Here’s the same calculation in an easier to follow format: So…. what’s the issue?

This may seem quite sensible so far, however the issue is with the wording. The following is an example of a fairly standard London Market wording, taken from an anonymised slip which I came across a few years ago. Priority: USD 10,000,000 each and every loss or an amount equal to the “Reinsured’s Portion’ of the total Original Insured Loss sustained by the original insured(s) of USD 200,000,000 each and every loss, whichever the lesser. … Reinsuring Clause Reinsurers shall only be liable if and when the ultimate net loss paid by the Reinsured in respect of the interest as defined herein exceeds USD 10,000,000 each and every loss or an amount equal to the Reinsured’s Proportion of the total Original Insured Loss sustained by the original insured(s) of USD 200,000,000 or currency equivalent, each and every loss, whichever the lesser (herein referred to as the “Priority”) For the purpose herein, the Reinsured’s Proportion shall be deemed to be a percentage calculated as follows, irrespective of the attachment dates of the policies giving rise to the Reinsured’s ultimate net loss and the Original Insured Loss: Reinsured Ultimate Net Loss / Original Insured Loss … The Original Insured Loss shall be defined as the total amount incurred by the insurance industry including any proportional co-insurance and or self-insurance of the original insured(s), net of any recovery from any other source What’s going on here is that we’ve defined the effective line to be the Reinsured’s unl divided by the 100% market loss. First problem From a legal perspective, how would an insurer (or reinsurer for that matter), prove what the 100% insured market loss is? The insurer obviously knows their share of the loss, however what if this is a split placement with 70% placed in London on the same slip, 15% placed in a local market (let’s say Indonesia?), and a shortfall cover (15%) placed in Bermuda. Due to the different jurisdictions, let’s say the Bermudian cover has a number of exclusions and subjectivities, and the Indonesian cover operates under the Indonesian legal system which does not publically disclose private contract details. Even if the insurer is able to find out through a friendly broker what the other markets are paying, and therefore have a good sense of what the 100% market loss is, they may not have a legal right to this information. The airline does have a legal right to the information, however the reinsurance contract is a contract between the insured and reinsured, the airline is not a party to the reinsurance contract. The point is whether the insurer and reinsured have the legal right to the information. The above issues may sound quite theoretical, and in practice there are normally no issues with collecting on these types of contracts. But to my mind, legal language should bear up to scrutiny even when stretched – that’s precisely when you are going to rely on it. My contention is that as a general rule, it is a bad idea to rely on information in a contract which you do not have an automatic legal right to obtain. The second problem The intention with this wording, and with contracts of this form is that the effective line should basically be the same as the insured’s signed line. Assuming everything is straightforward, if the insurer takes a x% line with a limit of Y bn. If the loss is anything less than Y bn, then the insured’s effective line will simply be x%*Size of Loss / Size of loss. i.e. x%. My guess as to why it is worded this way rather than just taking the actual signed line is that we don’t want to open ourselves to a issues around what exactly we mean by ‘the signed line’ – what if the insured has exposure through two contracts both of which have different signed lines, what if there is an inuring Risk Excess which effectively nets down the gross signed line – should we then use the gross or net line? By couching the contract in terms of UNLs and Market losses we attempt to avoid these ambiguities Let me give you a scenario though where this wording does fall down: Scenario 1 – clash loss Let’s suppose there is a mid-air collision between two planes. Each results in an insured market loss of USD 1bn, then the Original Insured Loss is USD 2bn. If our insurer takes a 10% line on the first airline, but does not write the second airline, then their effective line is 10% * 1bn / 2bn = 5%... hmmm this is definitely equal to their signed line of 10%. You may think this is a pretty remote possibility, after all in the history of modern commercial aviation such an event has not occurred. What about the following scenario which does occur fairly regularly? Scenario 2 – airline/manufacturer split liability Suppose now there is a loss involving a single plane, and the size of the loss is once again USD 1bn, and that our insurer once again has a 10% line. In this case though, what if the manufacturer is found 50% responsible? Now the insurer only has a UNL of USD 500m, and yet once again, in the calculation of their floating deductible, we do the following: 10% * 500m/1bn = 5%. Hmmm, once again our effective line is below our signed line, and the floating deductible will drop down even further than intended. Suggested alternative wording My suggested wording, and I’m not a lawyer so this is categorically not legal advice, is to retain the basic definition of effective line - as UNL divided by some version of the 100% market loss - by doing so we still neatly sidestep the issues mentioned above around gross vs net lines, or exposure from multiple slips, but instead to replace the definition of Original Insured Loss with some variation of the following ‘the proportion of the Original Insured Loss, for which the insured derives a UNL through their involvement in some contract of insurance, or otherwise’. Basically the intention is to restrict the market loss, only to those contracts through which the insurer has an involvement. This deals with both issues – the insurer would not be able to net down their line further through references to insured losses which are nothing to do with them, as in the case of scenario 1 and 2 above, and secondly it restrict the information requirements to contracts which the insurer has an automatic legal right to have knowledge of since by definition they will be a party to the contract. I did run this idea past a few reinsurance brokers a couple of years ago, and they thought it made sense. The only downside from their perspective is that it makes the client's reinsurance slightly less responsive i.e. they knew about the strange quirk whereby the floating deductible dropped in the event of a manufacturer involvement, and saw it as a bonus for their client, which was often not fully priced in by the reinsurer. They therefore had little incentive to attempt to drive through such a change. The only people who would have an incentive to push through this change would be the larger reinsurers, though I suspect they will not do so until they've already been burnt and attempted to rely on the wording in a court case and, at which point they may find it does not quite operate in the way they intended. |

AuthorI work as an actuary and underwriter at a global reinsurer in London. Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

Leave a Reply.