|

I'm currently studying for the IFoA ST7 - General Insurance: Reserving and Capital Modelling exam which I will be sitting in a couple of weeks time, I know, you're all jealous of what a great time I must be having right now.

The Institute publishes past papers on their website with specimen solutions which is really helpful, what is less helpful though are the comments that the Institute's examiner has decided to sprinkle through out the specimen exam solutions. I've collected some of the better ones: “many candidates seemed to have an incredibly superficial understanding of key concepts which fell over when they were asked to apply those concepts” “There were almost no reasonable answers to this part.” “Very poorly answered. Most candidates made only one or two points and these were often confused.” "Overall candidates displayed remarkable innovation in the range of ways in which they managed to get this question wrong." “Almost nobody made a reasonable attempt at this part.” “many candidates struggled with the mitigation question, displaying an excessive tendency to focus on cover changes that would clearly be at best inappropriate and at worst illegal for compulsory covers; these candidates were fortunate that the marking system does not allow negative marks to be given.” “A fairly straightforward calculation which very few got right.” It makes me warm and fuzzy to know that how highly the examiner thinks of us students. Taking the last comment as an example - is it perhaps evidence that the calculation is not in fact 'fairly straightforward' given 'very few got it right'? "I don't know what you mean by 'glory,' " Alice said. Humpty Dumpty smiled contemptuously. "Of course you don't—till I tell you. I meant 'there's a nice knock-down argument for you!' " "But 'glory' doesn't mean 'a nice knock-down argument'," Alice objected. "When I use a word," Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, "it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less." "The question is," said Alice, "whether you can make words mean so many different things." "The question is," said Humpty Dumpty, "which is to be master—that's all." I don't think Lewis Carroll had 'Big Data' or 'Machine Learning' in mind when he penned these words, however I think the quote is quite apt in this context. All to often these buzzwords seem to fall foul to the Humpty Dumpty principle, they mean just what the speaker chooses them to mean - regardless of what the words actually mean to anyone else. So what do these terms actually mean? Machine Learning The field of study which investigates algorithms that give computers the ability to learn without being explicitly programmed. What do we mean by ‘learn’ in this context? The definition used by Machine Learning practitioners, originally stated by Arthur Samuel is: "A computer program is said to learn from experience E with respect to some class of tasks T and performance measure P if its performance at tasks in T, as measured by P, improves with experience E." So what problems can Machine Learning algorithms be applied to? The main advances in machine learning have been in the following areas:

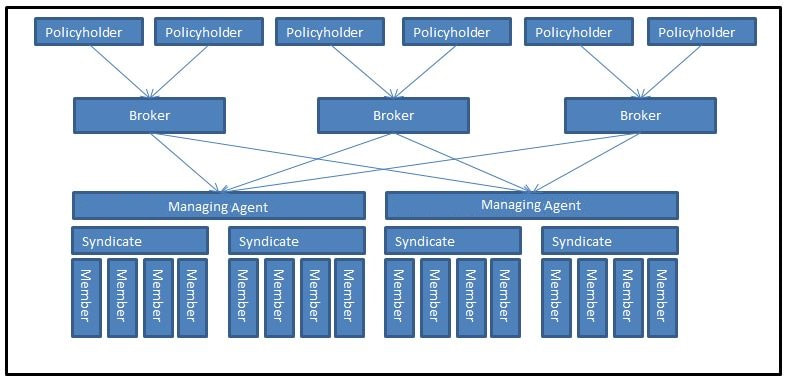

A trait shared by all these problems is that previously computers were thought to be incapable of tackling them. This is one reason why Machine Learning is such an exciting and growing field of study. If you'd like to know more about Machine Learning then Andrew Ng at Stanford University has released a really good free online course through Coursera which can be accessed through the following link: Big Data Big Data can be defined as data which conforms to the 3Vs. Big Data is available at a higher volume, higher velocity (rate at which data is generated) and/or greater variety than normal data sources. So for example, looking at an insurance company, claims data would not count as Big Data, the volume will be fairly low, velocity will be slow, and variety will be fairly uniform. The browsing patterns of an aggregator website on the other hand would count as Big Data. For example, the amount of time someone spends on Comparethemarket.com, their clicks, what they search for, how many searches they make, how often they return to the website before making a purchase, etc. would count as Big Data. There would be a massive volume of data to analyse and the data would be available in real time. (It wouldn’t meet the variety criteria, but that’s not a necessary condition) Due to the need to extract useful information from Big Data, and the difficulties created by the 3Vs, we cannot rely on traditional methods of data analysis. Given the volume and velocity of Big Data, we require methods of analysis that does not need to be programmed explicitly, this is where Machine Learning fits in. Machine Learning in the guise of speech and handwriting recognition can also be important if the data generated is in audio form but needs to be combined with other data. Data Mining Data Mining is a catch all term for the process of analysing and summarising data into useful information. Data may be in the form of Big Data, and methods used may be based on Machine Learning (where the algorithm learns from the data) or may be more traditional. Data Visualisation Data Visualisation is the process of creating visual graphics that aid in understanding and exploring data. It has become increasingly important for two reasons, firstly, the rise in the volume of data sets means that new methods are required to understand data, secondly, an increase in computing power means that more advanced visualisation techniques are now possible. Data Science Data Science is a broad term which encompasses processes which aim to extract knowledge or insight from Data. Data science therefore includes all the previous fields. For example, in carrying at an analysis, we will first collect our data, which may or may not be in the form of Big Data, we will then mine our data, possibly using machine learning, and then present our results through Data Visualisation. Background Lloyd’s or Lloyd's of London is an insurance marketplace located in the City of London. It developed out of an informal meeting of ship owners, merchants and sailors in Edward Lloyd's coffeehouse. The original coffeehouse first opened in 1688 making Lloyd's over 300 years old. Lloyd's really is a unique and interesting institutional, and there is really nothing else quite like it. For example, did you know that Lloyd's uses an accounting system that runs for thee years rather than the usual one year accounts that most companies use? Three years was the length of time that a 17th century ship took to circumnavigate the globe, and since most of the business written at Lloyd's during it's early years was Marine insurance, it was decided that it was a good idea to run the accounts for three years and it hasn't changed since. But how does Lloyd's work in practice? Who pays whom for what and how do they decide how much to pay? And how do people make money from all of this? Syndicates Syndicates are the basic building blocks of Lloyd's. The word syndicate just means a group of people and in the context of Lloyd's, a Syndicate is a group who are willing to collectively write insurance. Is there a name for the people who make up the Syndicate? Yes there is! They are called Members. The Members join together to form a Syndicate. Members come in many different forms, some will be individual investors, who might have a relatively modest net worth, others will be specialist insurance companies, set up specifically to write business at Lloyd's and worth billions of dollars. The word Member applies equally to both. Members which are set up as companies are called 'Corporate' members, and contribute the majority of the capital at Lloyd's. Individual investors in Lloyd's are called 'Individual Members', or 'Names'. Historically Names made up a majority of the capital, but they are less important now. Even though the Syndicate is the one who provides the insurance to the policyholder, they will not sell the insurance directly to the policyholder, instead a Syndicate will employ a Managing Agent (not to be confused with a Managing General Agent - MGA - which is a separate type of entity) to underwrite the insurance on its behalf. Some Managing Agents will deal with multiple Syndicates and some will deal with just one Syndicate. The Managing Agent will most often arrange the insurance through insurance brokers. That's quite a few different groups, so here's an image showing how they all fit together.

How do Members make money at Lloyd's?

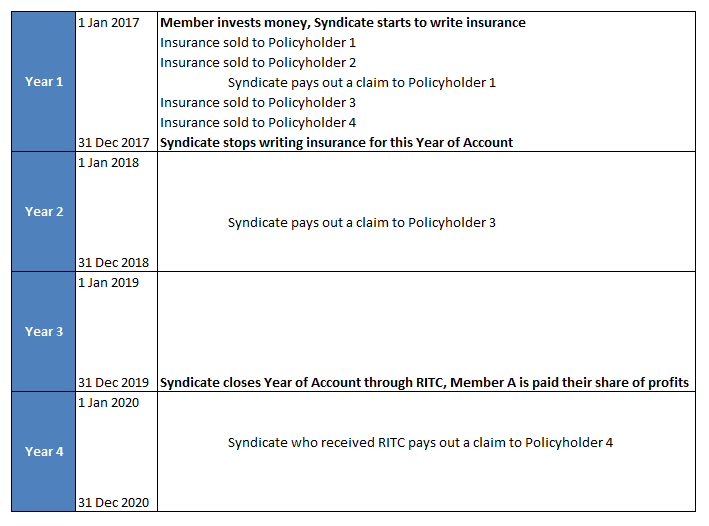

Members agree to write business at Lloyd's for one year at a time. A given year of account will then be kept open for three years. (Remember earlier when we mentioned that this was the length of time it took a 17th century ship to circumnavigate the globe, that's where this number comes from) At the end of the three years, the syndicate will settle up all the outstanding business through a process called Reinsurance to Close (RITC), and then all the profits or losses from all the from all the contracts the Syndicate has written in that year are shared among the members in proportion to the amount of capital they provided to the Syndicate. For example, suppose that in a given year Syndicate A made a profit of £10m and suppose that Member Z provided 2% of the capital that the Syndicate required that year. Then Member Z would receive a payment of £10m * 2% = £200,000. On the other hand, suppose that Syndicate A actually lost £10m over the year, then Member Z would be liable to cover their share of the loss, in this case, £200,000. Therefore all the Members of a Syndicate share in the fortunes of the Syndicate. Here is a graphic with a very simplified example showing a timeline of how this would work in practice.

How do Syndicates get business?

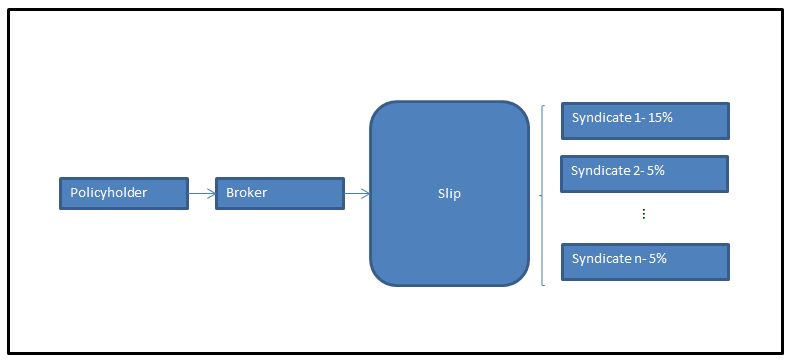

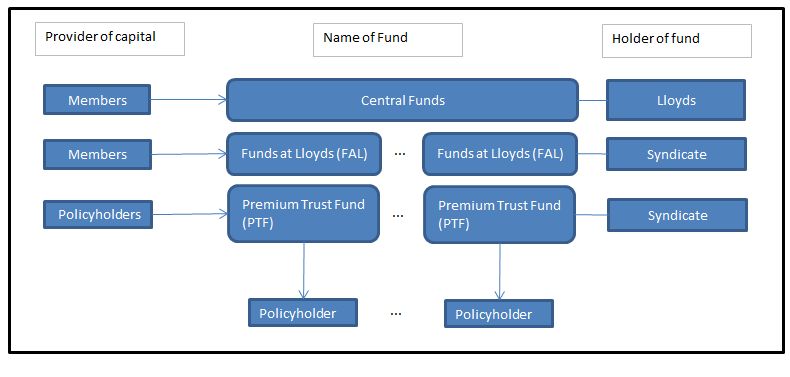

Business at Lloyd's is placed through insurance or reinsurance brokers. A policyholder will approach a broker and ask them to arrange an insurance contract at Lloyd's. The broker will then typically place the contract at Lloyd's through the 'slip system'. Slip System The broker will produce a 'slip' which contains all the details of the risk which is to be insured. For example, a slip might be a contract to insure a large industrial plant from fire damage. Syndicates (through their Managing Agent) may then decide to underwrite a percentage of the slip. What this means in practice is the syndicate will take a percentage of the premium, and then if there is a loss, they will be liable for a percentage of the insurance claim. For example a syndicate might take 5% of the risk. This means that they will receive 5% of the premium that the policyholder pays and be responsible for 5% of the claims arising from the contract if there is fire damage to the industrial plant. The process of spreading the risk around different syndicates is known as coinsurance. As an aside, this is where the term 'Underwriter' originally comes from. When an insurer writes a share of a risk (also known as 'taking a line on the risk'), they will sign their name at the bottom of the slip, along with the % share they are willing to write. Hence the term 'underwriter' - people who write their name under the text of the document. Isn't this unneccssarily complicated though? What's the point of everyone take a share? Why can't one syndicate just take on 100% of the risk? The answer is they can, and sometimes do, particularly for smaller risks. However it will probably be very hard to find a syndicate that is willing to take 100% of a very large risk. Going back to our industrial plant example, if the plant is worth hundreds of millions, the claim size could potentially be in the hundreds of millions too. Let's pause to think about what's going on here then. We saw in the previous section that all the members in a syndicate share the profits and losses from all the contracts that the Syndicate writes in the year, but we now have another type of sharing in the form of coinsurance. So for a given contract we might have a dozen syndicates all sharing the risk, and inside each syndicate we might have dozens of members also sharing the risk of their syndicate. Therefore each contract could potentially be shared by hundreds of members! The following graphic shows how the slip system works. Capital Requirements Any time an insurance contract is written, capital is required to cover the possibility that the claims might be larger than the premiums. Otherwise there is a risk that a policyholder might not be able to claim from the insurer if the insurer gets into financial trouble. Given the complicated way that business is written at Lloyd's, how do we decide how much capital to take from each member, and how is this capital held? The policyholder will pay a premium to the insurer in exchange for the insurer taking on the risk. We saw earlier that this premium will be spread among multiple syndicates depending on which ones sign the slip. Each syndicate will hold the premium it receives from policyholders in a Premium Trust Fund (PTF). The PTF will be a pool of all the premiums that the insurer receives throughout the year, rather than the Syndicate keeping separate funds for each policy written. What happens though if the claims are larger than the premiums across all the business written for the year? The syndicate will run out of money in their PTF and will need additional capital. To cover this possibility members will deposit 'Funds at Lloyd's' (FAL) with their Syndicate. For a given syndicate, if their PTF proves to be inadequate to cover claims, then the syndicate will have made a loss and the FALs will be used to make up the difference. What happens in the unlikely event that even the FALs are too small to cover the claims? To cover this eventuality, all members are also required to contribute a small amount every year to the Lloyd's central fund. This fund is only used to pay claims if the FALs for a given syndicate prove inadequate. The following graphic illustrates this process.

If you enjoyed this article, but would like to find out more, I have also written a FAQs about Lloyd's which can be accessed through the link below:

www.lewiswalsh.net/blog/faqs-about-lloyds-of-london |

AuthorI work as an actuary and underwriter at a global reinsurer in London. Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed