|

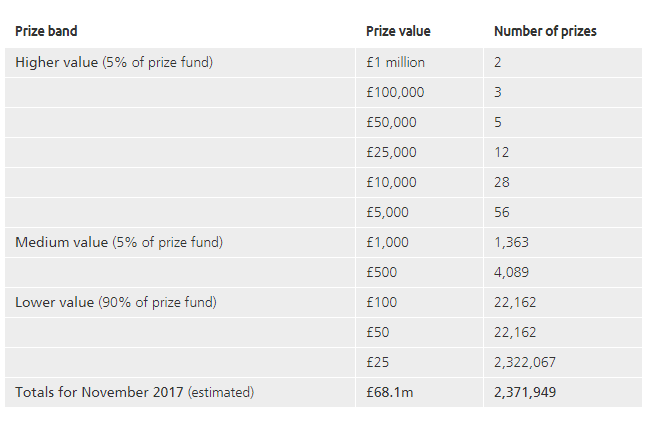

I've got to admit, up until recently, I never really understood why anyone would buy Premium Bonds. You get an expected return of 1.15%, which is well below other asset classes, there is significant volatility in returns, and the 1.15% is not even guaranteed, i.e. it's possible you'll never get any returns at all. The risk and return profile just seem completely out of sync with the alternatives. But after speaking to my Grandad about them yesterday, I started to understand why some of the soft factors make them so attractive to savers. Then when I was mulling over it further, I realised that these soft factors would actually be seen as negatives when viewed through the lens of Modern Portfolio Theory. What are Premium Bonds? Premium Bonds were introduced by Harold Macmillan in 1956 in an attempt to encourage individuals to save more, and also to help raise money to finance Government spending. The bonds pay out prizes to bondholders based on a lottery system and are organised by the National Saving and Investment Agency. The Government uses the money to help finance the Public Sector Borrowing Requirement (the difference between the amount of tax the Government collects .every year, and the amount the Government spends - which has been negative for about 30 years now!) Every month, the NSI distributes a prize pool randomly among Bond holders, the pool is calculated so that the total annual amount paid out is equivalent to 1.15% of the total value of bonds held over the year. So as there are approximately £71bn of bonds owned in total, the prize pool will be £71bn * 1.15% = £817m per year, or £68.1m per month. This £68.1 million will then be distributed randomly to bond owners in various sized prices using the following table: Both the interest rate used to calculate the overall prize pool, and the distribution of prizes is updated from time to time, to account for changes in the overall market conditions. This table is correct as at the date of this post. Advantages of Premium Bonds In spite of their relatively low rate of return, Premium Bonds do a have a number of features that make them attractive to individual savers:

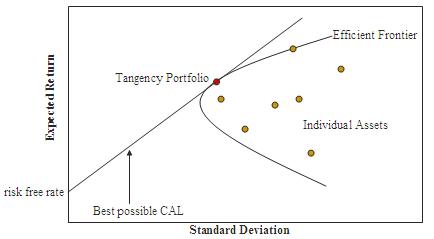

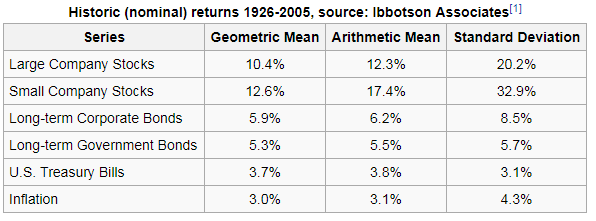

For many individual investors, the first five bullet points are extremely important. I think many savers would even say that are necessary requirements to get them to invest their money. It's the final bullet point which is particularly interesting though, the possibility of winning £1 million is a big selling point of Premium Bonds. This should interest any analyst who uses conventional theories of investment, as most investment theories would consider this a downside of Premium Bonds. To understand why this is the case, we'll need to take a brief look at Modern Portfolio Theory. Volatility of Investment Returns as a Risk Measure All the possible investment classes have different risk and return profiles. Some provide high returns, but also contain high levels of risk. Others offer lower levels of return, but also come with less risk. In order to compare different investment classes in a consistent way, we need a single definition of risk and return which we can then apply to each class. The obvious measure to use for return is simply the Mean Expected Return. The situation isn't so straight forward for our risk measure though. There is no perfect measure of risk, and all the possible measures have advantages and disadvantages. In practice, the most commonly used measure is variance of return and this is the approach used in Modern Portfolio Theory: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modern_portfolio_theory Under Modern Portfolio Theory, we calculate the expected return of each investment class, along with the variance of return and plot this on a graph. An investor is then assumed to want to maximise the expected return, while minimising the variance of returns (because this corresponds to risk). This allows us to construct an 'efficient frontier' corresponding to those investments, which for a given return, minimise the risk. The following graph demonstrates this analysis. By including the possibility of winning a £1 million prize, we are massively increasing the variance of the investment returns, but since the overall return is calibrated to a 1.15% expected return, the risk-reward profile of premium bonds (using variance as our measure of risk) looks terrible. So we end up with the strange situation that one of the main selling points of Premium Bonds - the possibility of winning a £1 million prize each month, actually should make the investment less attractive under most theories of investment. I did a quick calculation of the variance of returns provided by premium bonds, and it comes out at a whopping 35,000%. Most of this volatility is coming from the fact that two of the prizes are for £1 million, if we take out all the prizes above £1000 and reallocate the money to the smaller prizes the volatility reduces by about 400 times, down to around 90%. But even this is still considered very volatile compared to most investment classes. For example, Burton Malkiel in A Random Walk Down Wall Street provides the following table of historic asset class returns with accompanying volatility (which I then copied from Wikipedia) So for comparison, we see that according to this analysis, investing in Small Companies Stocks provided an average return of 12.6%, much higher than premium bonds, yet only had a Standard Deviation of return of 32.9%. Under the assumptions of Modern Portfolio Theory, by using variance of investment returns as a risk measure, we would conclude that investors would prefer not to have the possibility of the £1 million prize, but instead would prefer to have more smaller prizes included in the payout. This is clearly not the case. Disadvantages of investing in Premium Bonds So far we've talked about the advantages of investing in Premium Bonds, and we've also talked about how some of these selling points go against the conclusions of Modern Portfolio Theory (though I think this might say more about the state of Modern Portfolio Theory than Premium Bonds). Are there however any clear disadvantages to investing in Premium Bonds? I think there are, and here are a few of them:

We often distinguish between real and nominal investment returns when analysing investment classes. What this means is that some investment classes provide returns which are expected to be above inflation, other classes provide returns which are of a fixed amount and may be greater than or smaller than the level of inflation in the economy, these are called nominal returns. To see what we mean by this, let's say you invest £1,000 in premium bonds in a given year and you get £25 in prizes, leaving you with £1,025 at the end of the year. Let's assume also that prices (i.e. inflation) went up by 5% during the year, which means that in order to buy something which would have cost £1,000 at the start of the year, you would now need £1,050. So your £1,025 which you got back from the Premium Bonds at the end of the year, can now buy less than the £1,000 you put in originally. So that even though you've now got more money, the real return on your investment was negative. Premium Bonds are currently paying out at 1.15%, whereas inflation in July 2017 was 2.6% according to the Office of National Statistics. This means that you are in effect losing money by holding Premium Bonds.

Due to the lottery structure of Premium Bond returns, it's possible (and in fact highly likely unless you hold large quantities of bonds) that you will get no investment returns at all. For example, someone who holds £100 of Premium bonds has a 96% chance of not getting any prizes at all in a given year. This is in contrast to a fixed interest bank account, for example if it guarantee to pay 3% pa there would be no possibility of winning a £1 million prize, but which you could be certain would always give you your 3% return at the end of the year. If you are willing to go through the hassle of shopping around for a savings account which does guarantee 3%, then you'd probably be better off from a financial perspective investing in the savings account and then buying yourself a lottery ticket every week rather than investing in premium bonds.

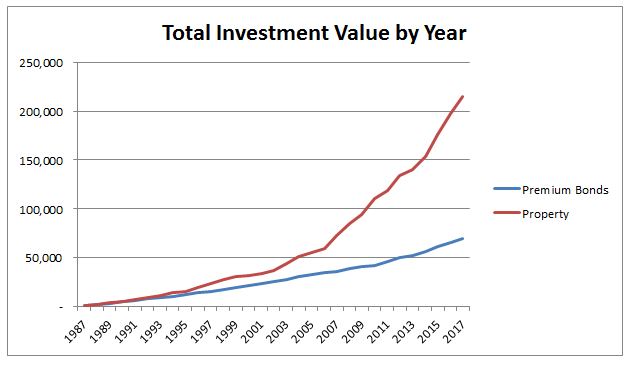

The expected return from Premium Bonds is much lower than the returns we could expect from other investment classes. To see how much of a different this can make, let's take two hypothetical savers, both of whom have been saving £100 per month for the last 30 years, one has been investing in Premium Bonds (and getting an average return of 3.5% pa) and another has been investing in a Property Fund (and getting a 10% average return). Over the years, the difference between these two expected returns can have a significant impact on the overall amount that they save. I ran a quick simulation of this with some volatility producing the following graph: So we've talked about the positives and negatives of Premium Bonds, and also touched on some inconsistencies between the marketing of Premium Bonds, and how they would be viewed using traditional finance techniques. Are there any other features of Premium Bonds which are interesting? One quirk of Premium Bonds which seems to have captured people's imaginations is ERNIE. So who is ERNIE? E.R.N.I.E ERNIE stands for Electronic Random Number Indicator Equipment, and is the name of the machine that is used to randomly select which bonds win, Due to the fact that Premium Bonds were first set up in 1957, creating a computer to generate random numbers was a non-trivial problem at the time. ERNIE was developed in the Post Office Research Station in North West London. Despite its quaint sounding name, the Post Office Research Station was actually at the forefront of computing research during the 40s and 50s. The Colossus, the world's first electronic programmable computer, which had been developed during the second World War to help break one of the codes used by the Axis was developed at the Post Office Research Station. The details of Colossus were classified until the 1970s so it had limited impact on most other computers built around in the 50s and 60s, however the design of ERNIE was heavily influenced by the work that had been done on Colossus during the war as the same design team worked on both. Unlike most computers today that are pseudo-random number generators, ERNIE was a true random number generator. It contained neon tubes, through which an electric current was passed. Due to the electrons bumping into the neon atoms as they passed through the neon tube, the current leaving the neon tube varied randomly. This randomness was due to millions of tiny interactions between the electrons and the neon tube and was a source of true statistical randomness. This randomness was then calibrated so that ERNIE would select a collection of random numbers between 1 and 100 million, which corresponded to the Premium Bond numbers that people had purchased. I struggled to follow a lot of the technical details of how ERNIE works, due to an insufficient knowledge of electrical engineering, but if you are interested the following link contains a technical document describing how ERNIE selected random numbers: www.tnmoc.org/sites/default/files/Ernie-technology.pdf I might do some reading up on Electrical Engineering at some point, and then write up exactly how ERNIE worked, because I couldn't find a decent non-technical description online. Conclusion Premium Bonds were a massive success when they were launched. They managed to get people excited about saving, and they gave the Government a cheap source of borrowing. I think it's a shame they have fallen by the wayside in recent years. They are conceptually simple, they offer a lot of the guarantees that savers look for in an investment opportunity - protecting their capital, not locking them in for a fixed period - they exploit the popularity of lotteries in a positive way (by tricking people into saving more in order to play), and they don't require complicated decisions to be made by savers (who has time to trawl through the bewildering array of different options currently available - Cash ISAs, Stocks and Shares ISAs, NSI bonds, Fixed interest bank accounts....) All too often, it seems Government savings schemes are designed by individuals steeped in financial theory who are too far removed from the savers who will be using the products. We should rethink how we design the kind of products offered by the NS&I and take more account of Behavioural Economics, and Marketing Strategies rather than relying on microeconomic models which assume rational investors, or relying on models of investment returns like Modern Portfolio Theory. |

AuthorI work as an actuary and underwriter at a global reinsurer in London. Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

Leave a Reply.