|

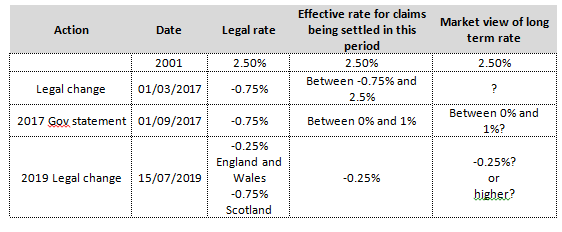

If you are an actuary, you'll probably have done a fair bit of triangle analysis, and you'll know that triangle analysis tends to works pretty well if you have what I'd call 'nice smooth consistent' data, that is - data without sharp corners, no large one off events, and without substantially growth. Unfortunately, over the last few years, motor triangles have been anything but nice, smooth or consistent. These days, using them often seems to require more assumptions than there are data points in the entire triangle. So how exactly have we got into this sorry state of affairs? To tell this story, we need to go back a few years. Ogden The year is 2017, the Ogden discount rate is 2.5%, and the intersection of people worrying about global pandemics and people who regularly wear tin foil hats is not negligible. Then the government comes along and shockingly sets the discount rate at the exact level implied by the clearly defined calculation methodology they have always used. This lead to an Ogden level of -0.75%. This immediately created a step change in incurred claim triangles, lump sums which were due to be paid at this point should have started to be settled at a -0.75% discount factor, creating a large uplift on that implied by the previous 2.5% Ogden rate. Unless you believe the discount rate is going to be slashed by the same amount every year, when using a triangle, this step change needs to be removed from your development pattern and adjusted for separately. Why did I say claims should have been settled at this rate rather than were settled at this rate? Well reality is often messier than we would like. Motor insurers were on the whole unhappy with the announcement and had a number of different responses: ‘surely the government didn’t really mean to set it at this level? Let’s meet in the middle somewhere.’, ‘okay, Mr Claimant, I’ll use -0.75% as the discount rate, but I’m going to fight you on other costs to partially offset this increase, ultimately this is still a negotiation’ ‘listen, I know the rate is -0.75% now, but we both know the government is probably going to change it to something higher soon, so you’ve got two options, meet me in the middle and accept a lower number, or I’ll drag out the case for a year or so until the rate is changed back and then settle at that lower rate.’ The end result was that lump sums were being settled at a range of effective discount rates which varied anywhere between -0.75% and 2.50%. If you have losses in your triangles settled in this six month window, who knows exactly how you should adjust them? The next development was in September 2017, the government seeing the issues their change had made, stepped up and released a statement announcing they intended to review the methodology used to set the rate, and that the new rate, using the updated methodology would most likely end up in the range 0% to 1%. (the government didn’t explain the new methodology, but you can bet we then tried to back-in various guesses to see what they might have picked so as to get this range) So people immediately started pricing business at 0.5% right? Well not quite. If the Ogden rate changes today and your company takes a big reserve hit, your CFO is going to want payback asap, he’s not going to care that there’s a five year tail on large bodily injury claims, therefore the premium we are charging now should be set against the expected Ogden rate at payment date, which is now no longer -0.75%, but is 0.5%, and may even end up less in 5 years time, etc. etc. etc. If the Ogden rate changes then it turns out the market reacts pretty sharpish. Okay, so you decide to amend how much premium you are charging in order to get payback on the hit you just took. But the hit you took is going to vary substantially by insurer, and as much as you;d like payback, you also like market share. One thing that might protect you is that XoL costs (for those with XoLs that is) will not change immediately, but rather whenever the renewal comes round. Therefore reinsurers will feel the pain immediately but direct writers will feel the pain of increased RI spend at a staggered pace throughout the year (though many will be clustered around 1/1). So different people are reacting in the market at different times, and different people require different levels of payback and are able to be more protective of market share. Oh and by the way England and Scotland have different rates now. So you need to blend your rate based on where the underlying business is based, sorry! This is a new issue for business being written, but in a few years it will be yet another adjustment to make to triangles as claims start to be settled at differential rates. Here is a very messy table which summarises the very messy reality of how some of these factors changed over time. So why do I bring all this up?

A few months ago, if someone sent you a motor triangle to analyse, you could probably just about manage to do something sensible about the issues highlighted above. If you were not interested in large losses, hopefully you'd have enough info to strip them out. By the end of the analysis your triangle probably ended up looking like a rather strange colour-by-numbers picture from all the manual amendments, but at least it (probably) gave sensible answers. And then the coronavirus came along. Lockdown changes Following the Government lockdown on 23rd March, pretty immediately claim frequencies dropped a lot. It’s unclear exactly where the ultimates for these lockdown (and the coming semi-lockdown) weeks/months will settle, I expect in the fullness of time we will see that part of the drop off is due to reporting patterns stretching out (customer behaviour, slow down at legal firms, delays at TPAs and in claims teams) There are a few pieces of information we can look at though. Firstly, if you have access to motor triangles then you can just look at how claim frequencies have changed recently and then adjust somewhat with a few assumptions about how development patterns may have changed – which I’ve done where I can, but won’t go into specifics… proprietary info and all that. The other piece of information is to look at the premium credits various insurers have announced, and what this must imply about their view of how their ULR has changed. Dowling and Partner’s IBNR weekly published a good analysis of this. Taking Progressive as an example, who announced a credit of 20% of gross premium for two months, which when converted into a loss cost, is consistent with approximately a 30% reduction in claim frequency. My personal opinion is that this figure of 30% may be on the conservative side of the actual reduction, if for no other reason than no one knows exactly what will happen later in the year, and insurer's are probably erring on the side of caution in terms of giving premiums back. For example, here are a couple of scenarios off the top of my head where insurers actually end up worse off.

So where does this leave our unfortunate motor triangles? The way this will probably play out is that on top of any Ogden related adjustments, we will need to make adjustments for:

So what's an actuary to do? Wouldn’t it be nice if as a profession we could all agree to ignore the last three years of data and do all our projections off 2016 and prior? Sure it would be a lot less accurate, but it would definitely be a lot simpler, and as long as we’re all doing it, no one will be at a competitive disadvantage. |

AuthorI work as an actuary and underwriter at a global reinsurer in London. Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

Leave a Reply.