Piketty also adds colour by tying his observations to the literature written at the time (Austen, Dumas, Balzac), and how the assumptions made by the authors around how money, income and capital work are also reflected in the economic data that Piketty obtained.

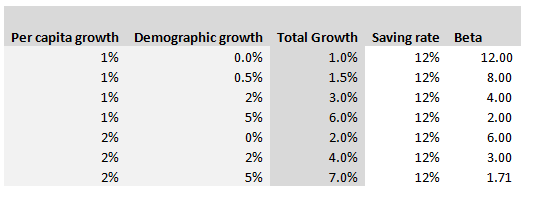

Hopefully I've convinced you Piketty's programme is a worthwhile one, but that still leaves the fundamental question - is his analysis correct? That's a much harder question to answer, and to be honest I really don't feel qualified to pass judgement on the entirety of the book, other than to say it strikes me as pretty convincing from the limited amount of time I've spent on it. In an attempt to contribute in some small way to the larger conversation around Piketty's work, I thought I'd write about one specific argument that Piketty makes that I found less convincing than other parts of the book. Around 120 pages in, Piketty introduces what he calls the ‘Second Fundamental Law of Capitalism’, and this is where I started having difficulties in following his argument. The Second Fundamental Law of Capitalism The rule is defined as follows: $$ B = \frac{s} { g} $$ Where $B$ , as in Piketty’s first fundamental rule, is defined as the ratio of Capital (the total stock of public and private wealth in the economy) to Income (NNP): $$B = \frac{ \text{Capital}}{\text{Income}}$$ And where $g$ is the growth rate, and $s$ is the saving rate. Unlike the first rule which is an accounting identity, and therefore true by definition, the second rule is only true ‘in the long run’. It is an equilibrium that the market will move to over time, and the following argument is given by Piketty: “The argument is elementary. Let me illustrate it with an example. In concrete terms: if a country is saving 12 percent of its income every year, and if its initial capital stock is equal to six years of income, then the capital stock will grow at 2 percent a year, thus at exactly the same rate as national income, so that the capital/income ratio will remain stable. By contrast, if the capital stock is less than six years of income, then a savings rate of 12 percent will cause the capital stock to grow at a rate greater than 2 percent a year and therefore faster than income, so that the capital/income ratio will increase until it attains its equilibrium level. Conversely, if the capital stock is greater than six years of annual income, then a savings rate of 12 percent implies that capital is growing at less than 2 percent a year, so that the capital/income ratio cannot be maintained at that level and will therefore decrease until it reaches equilibrium.” I’ve got to admit that this was the first part in the book where I really struggled to follow Piketty’s reasoning – possibly this was obvious to other people, but it wasn’t to me! Analysis – what does he mean? Before we get any further, let’s unpick exactly what Piketty means by all the terms in his formulation of the law: Income = Net national product = Gross Net product *0.9 (where the factor of 0.9 is to account for depreciation of Capital) $g$ = growth rate, but growth of what? Here it is specifically growth in income, so while this is not exactly the same as GDP growth it’s pretty close. If we assume net exports do not change, and the depreciation factor (0.9) is fixed, then the two will be equal. $s$ = saving rate – by definition this is the ratio of additional capital divided by income. Since income here is net of depreciation, we are already subtracting capital depreciation from income and not including this in our saving rate. Let’s play around with a few values, splitting growth $g$, into per capita growth and demographic growth we get the following. Note that Total growth is simply the sum of demographic and per capita growth, and Beta is calculated from the other values using the law.

So why does Piketty introduce this law?

The argument that Piketty is intending to tease out from this equality is the following:

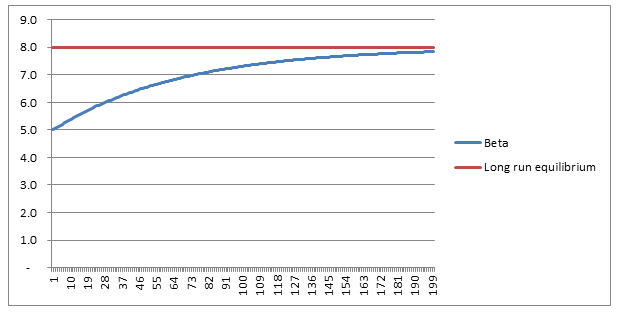

In fact using $g=1.5 \%$ as a long term average, we can expect Beta to crystallise around a Beta of $8$! Much higher than it has been for the past 100 years. Analysis - convergence As Piketty is quick to point out, this is a long run equilibrium towards which an economy will move. Moreover, it should be noted that the convergence of this process is incredibly slow. Here is a graph plotting the evolution of Beta, from a starting point of 5, under the assumption of $g=1.5 \%$, $s = 12 \%$:

So we see that after 30 years ( i.e. approx. one generation), Beta has only increased from its starting point of $5$ to around $6$, it then takes another generation and a half to get to $7$, which is still short of its long run equilibrium of $8$.

Analysis - Is this rule true? Piketty is of course going to want to use his formula to say interesting things about the historic evolution of the Capital/Income ratio, and also use it to help predict future movements in Beta. I think this is where we start to push the boundaries of what we can easily reason, without first slowing down and methodically examining our implicit assumptions. For example – is a fixed saving rate (independent of changes in both Beta, and Growth) reasonable? Remember that the saving rate here is a saving rate on net income. So that as Beta increases, we are already having to put more money into upkeep of our current level of capital, so that a fixed net saving rate is actually consistent with an increasing gross saving rate, not a fixed gross saving rate. An increasing gross saving rate might be a reasonable assumption or it might not – this then becomes an empirical question rather than something we can reason about a priori. Another question is how the law performs for very low rates of $g$, which is in fact how Piketty is intending to use the equation. By inspection, we can see that:

As $g \rightarrow 0$, $B \rightarrow \infty $.

What is the mechanism by which this occurs in practice? It’s simply that if GDP does not grow from one year to the next, but the net saving rate is still positive, then the stock of capital will still increase, however income has not increased. This does however mean that an ever increasing share of the economy is going towards paying for capital depreciation.

Conclusion

Piketty’s law is still useful, and I do find it convincing to a first order of approximation. But I do think this section of the book could have benefited from more time spent highlighting some of the distortions potentially caused by using net income as our primary measure of income. There are multiple theoretical models used in macroeconomics, and it would have been useful for Piketty to help frame his law within the established paradigm. |

AuthorI work as an actuary and underwriter at a global reinsurer in London. Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

Leave a Reply.